Year 48, Kali yuga

15 years before present day

“We must be near Nīrmukku,” remarked Jayan, shielding his eyes from the low sun. He looked east, the towering peaks of the Kāhaigirī range shone like gold. “Yes, we are definitely around Nīrmukku. We could shelter in those temple ruins for the night.”

“Seri, we will continue the hunt tomorrow. Hopefully the dawn will bring with it some fresh luck.” Semmaḷvarāyan wiped the sweat from his face. “One of you halfwits had better know the path.”

“I do, prabhu!” one of the soldiers piped up from the back.

Semmaḷvarāyan gestured at the vast swampland around them. “Lead the way, your highness.” he mocked.

The soldier hurriedly nudged his horse to the front. They slowly made their way through the soggy land. It was slow going, the horses quickly tired, they had to stop often. The sun steadily made its way towards the horizon.

Semmaḷvarāyan broke the silence. “Yappa, rāsā!” he called from the back. “Did you not say you knew the way? This just feels like we are going in circles!”

“No, no, prabhu. See those kavvaka trees? Beyond that clump we should reach the river. Cross that, and we will be in Nīrmukku.”

“All this for a lousy boar.” Semmaḷvarāyan swatted a mosquito on his arm.

Soon, they arrived at the banks of the Settrāru. It was a muddy, slow moving river, more slush than water. They stood at the edge, staring at the eddies, trying to discern the shallow areas from the deeper pools.

“Look!” Jayan called out.

A frail old man in a small coracle on the opposite bank, waved a piece of cloth in the air, trying to get their attention. He pointed further down the river, where a narrow sandbar protruded a good way into the river.

“Finally!” Semmaḷvarāyan urged his horse towards the sandbar. The group crossed and Jayan walked up to the old man. “I thought Nīrmukku was abandoned. What are you doing here, thatha?”

Semmaḷvarāyan pushed past Jayan. “Questions you can ask later, Jayā. Let’s hope he has some food.”

The old man turned and hobbled away, leaning on his walking stick. “Come, come. Bring your horses to the hut. There’s fresh water and some old bales of hay.”

They followed the old man to the dilapidated hut. There was a small wood fire going outside, and they tied horses to the side, and sat around the flame. The old man ducked inside the tiny hut, and came out with a wicker basket. “These sandy waters are good for eels, did you know?” He dropped the basket by the fire, it was overflowing with grey, slimy catch. “These I sell at Maṇchērī and Vaẓhukkur, but I am happy to share them with any Eyinar clansman I come across.” he grinned, displaying his crooked stained teeth that stood out in all possible angles.

Semmaḷvarāyan looked back with mild surprise, but hid it quickly. “What is your name, thatha?”

“Esakkī, they call me.”

“How did you know I am an Eyinar?”

Esakkī pulled out a small knife, and began to chop the eels faster than their eyes could keep up. “All my brothers and father fought for your family against the hill tribes, did you know? It was long back, in the good old years when an Eyinan could walk with his head held high.”

“Watch your words!” Jayan stood up angrily. “Apologise to your warlord!”

Esakkī did not look up from chopping the eels. His fingers continue to move with great dexterity, belying his age. “Yes, yes, warlord, but not king, no?”

“You dare disrespect him?” Jayan gnashed his teeth.

“Quiet, Jayā. The old man does have a sharp tongue, but it speaks the truth. And do not threaten the man preparing your food!” Semmaḷvarāyan chuckled.

Jaya sat down, still glaring at the aged fisherman, who was now salting the eels.

Esakkī tossed an eel head over his shoulder. “How glorious was your grandfather, rāyarae! The Eyinar clan was feared and respected by all across the Verumvayal plains...but now, look at you, thambi—spent an entire day hunting, and now having to settle for bland swamp eels.”

Semmaḷvarāyan smiled wryly. “That’s enough salt, old man.”

Esakkī smiled, his crooked teeth visible. “Yes, yes. Pay no heed to this rambling old fool. But would I like to once again see the Eyinars rise to the status of kings and emperors? Yes, yes, I would.”

“Do tell us, thatha, how would we do that?” Jayan sneered.

“Ah, that is easy. The Thattān kingdom is weak.”

Jayan scoffed loudly.

The fisherman continued: “Ah, yes yes. Their heir was a stillborn, did you know? Karkōttai is in shambles, still recovering from their civil wars. Should be easy prey for a wily warrior.”

Jayan pursed his lips. “That was a decade ago—Karkōttai is being rebuilt as we speak.”

“Yes, yes, army is not at home, no?”

Semmaḷvarāyan looked up, amused.

“Karkōttai is the key to controlling the entire coast and its trade routes.”

Jayan spoke up again. “Indeed, let us walk into the Thattān heartlands and demand the throne. Are you senile, old man? They are no ordinary adversaries.”

Esakkī stoked the small fire. “That simply means you think less of yourself, boy.”

Jayan swore under his breath. His hand gripped his dagger on his waistband, and gritted his teeth. Semmaḷvarāyan glared at Esakkī, but Esakki continued to poke at the twigs, smiling with all of his crooked teeth glowing in the light of the fire.

——

A pond heron clucked loudly in the reeds by the misty shore, and Semmaḷvarāyan awoke with a start. He rubbed his eyes, and sat up. His men were still asleep, scattered around the long spent fire. The sky was still grey, but the peaks of the Kāhaigirī were beginning to turn bright gold.

He stood up and walked absently to the muddy bank. This fisherman and his tongue, he smiled to himself. But he spoke the truth, did he not? I am a shadow of my grandfather and his fathers, am I not? They were respected warriors, and had fought the Kuravar tribes and drove them from the plains and into the hills, claiming lands that were rightfully theirs—and here I am, getting educated in statecraft from a decrepit old fisherman.

Jayan walked up from behind, and yawned loudly. “Esakkī is nowhere to be seen, his coracle isn’t here, too. Must have left for Maṇchērī before dawn.”

Semmaḷvarāyan did not hear him, he was lost in thoughts, his mind in the grip of a vague itch of larger aspirations.

Read next—

Chapter 27 — Shape shifter

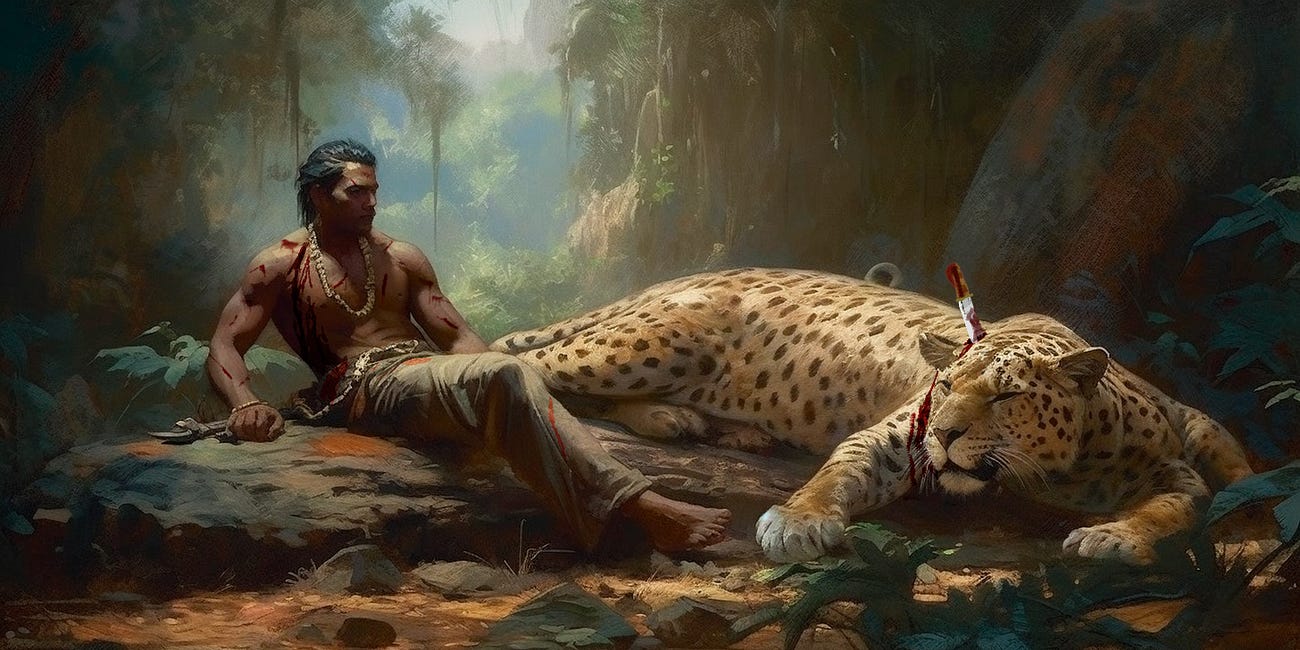

Year 2291, Dwapara yuga 173 years before present day Malasāra remained invisible, and watched the wounded hunter. A large leopard lay dead beside the man, a long blade sticking out from its great neck. He winced as he struggled to sit up. A deep gash ran from his shoulder to his waist. Blood trickled from the innumerable cuts on his body. He grabbed at a n…