Year 63, Kaliyuga

Present day

It was a hard ride back to the capital, Mārthāndan and Ripunjaya taking only short, occasional breaks. Time was of essence. As they neared the capital, Mārthāndan sent a passing patrol racing back to the capital with a message to get the War Council ready. They then rode straight to the barracks, and Mārthāndan began to prepare his men in anticipation.

Ripunjaya waited in his tent, tired, and anxious. He heard footsteps outside, and looked up as the door flap opened. A head appeared in the gap. It was Ilarāyan, one of Mārthāndan’s captains. “There you are. Come, come, Mārthāndan asked us to join him in the palace.”

“The palace?” Ripunjaya put down the dagger and the strop.

“The Council is about to begin, and he wanted us there. Quickly!”

Ripunjaya got up and followed Ilarāyan as they strode towards the gates. “Do you know what they are planning, Rāya?” asked Ripunjaya.

“Likely an attack on Pulithēvan’s hideout. The exact details, the meesaikārar is still deliberating.” Ilarāyan replied. ‘Meesaikārar’ was what the soldiers genially called Mārthāndan, because of his large moustache. “We have to put an end to these valippari thieves soon, they are hurting our commerce with the neighbouring kingdoms. Chieftain Vēlan’s discovery of the hideout has come at an apt time. Mārthāndan has planned an attack on their camp soon.”

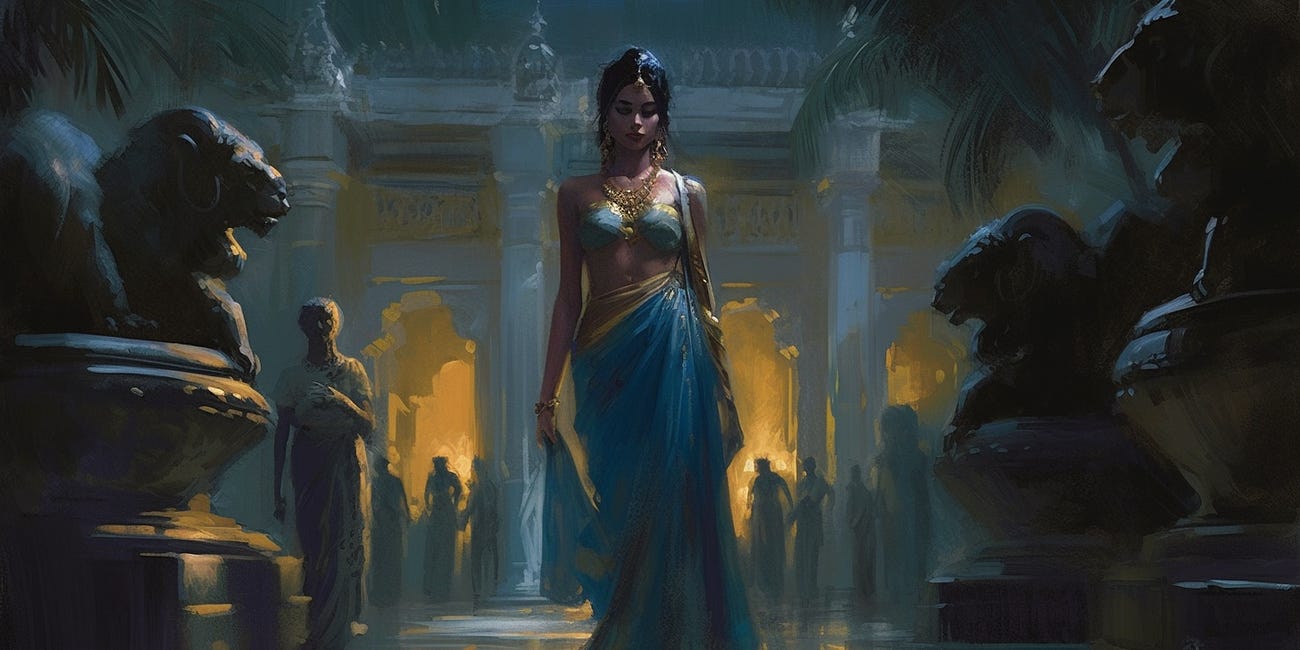

They reached the palace. They climbed the large wide steps and walked inside. This was Ripunjaya’s first time inside the palace, and the opulence awed him. The marble steps led to a large hall, and great stone pillars on the sides, sculpted in the form of a soldier, holding up levels above with his hands. In the centre was a stone tank filled with clear water, and brightly coloured fish swam lazily among the reeds. Small flowing streams kept the water bubbling, and the fish danced around the marble figurines along the sides.

Vast silk banners hung from the ceiling, each with a different sigil, and the walls were lined with ornate statues of gods and goddesses. From deep inside, slow melodious music floated through the halls. On the sides, long corridors with smooth stone floors stretched long and unbending. These corridors opened up to different rooms, each barred with heavy wooden doors, intricately carved with more figurines. Guards with stern faces were posted at every door, and servants rushed about their duties like bees in a hive.

They walked past the central hall, and to the rooms toward the side. They climbed a short flight of stairs, and walked along the corridor again, going further into the palace. They approached one of these rooms with a slightly larger and more ornate door, with six guards instead of the usual two. Seeing Ilarāyan, the guards outside took a step aside, allowing their entry. They looked curiously at Ripunjaya, still in his muddy riding attire.

Inside was a large table, with a handful of people around it. They saw Mārthāndan, he was staring intently at a map of Karkottai and its surroundings on the table. He saw them enter, and gestured them to come stand by him.

“This is the War Council, Ripunjaya,” Ilarāyan said in a low voice, looking around the room. “Except the Prince, who should join us shortly.”

The War Council consisted of half a dozen of the highest officials in the land. Mārthāndan was one, the Commander-in-Chief. He had proved to be a loyal servant of the kingdom from his young age, and the royal family trusted him with their lives.

Nerivānan was the Mahāmantri, the Prime Minister, and utterly loyal to the Crown, serving in this role for many decades. His father had been the Prime Minister before him. Nerivānan grew up in forests with Kumudhan, and had helped raise Aranvēndhan from his birth. He was Kumudhan’s closest advisor, and a dear friend.

Next was Vagaimāran, the General of the army, and had proved his worth alongside Aranvēndhan and Mārthāndan in their many battles. Plucked from one of the tribal clans, he had been instrumental in innumerable campaigns, and had grown to be an able general of the Thattān forces.

Thiruvāsagan was the Chancellor, who had started as a petty merchant on the streets, but fate had not kept him there for long. His astute mind and hard work enabled him to grasp opportunity after opportunity, and had eventually gained the favour of Kumudhan, who had kept him close ever since.

Also on the Council was the Royal Priest, Kalikāman, a reticent old man with a severe gaze. Wise and learned, he served in the Council as an observer and almost never spoke unless asked a direct question.

The final member was the Crown Prince Aranvēndhan himself, the head of the Council, and presided over all gatherings. He had already taken over the reins of the kingdom, and his monarchy remained just a formality. Kumudhan was no longer involved in the daily affairs of the state, but still offered advice to his son when needed.

The noblemen around the table seemed deep in thought, their expression sombre. They occasionally spoke in low whispers amongst themselves. A roll of parchment changed hands. Presently, the guards at the door announced the Prince’s arrival, and the people at the table stood up.

Rājakumaran Aranvēndha Thattān was tall and gaunt, and walked with his head held high. He wore an ornate gold crown, and its studded gems shimmered in the morning light. He had deep set eyes that were framed well by his dark brows and angular nose. His bow-shaped moustache was trimmed well. His lean, muscular torso was unclothed, save for the red silk cloth draped about his shoulder. The many battle-scars on his body seemed to add to his stature, and only made him more handsome. He wore golden necklaces set with gemstones, and an upavīta thread made of fine silver. His arms were adorned with gold bands, and wore two rings on each hand. The antariya was also silk, but in white, and shoes made of dark leather. He walked nimbly, with the springy gait of a much younger man.

The Council stood up and bowed with respect as he walked up to the table. He acknowledged them and seeing Mārthāndan, smiled and embraced his friend. He sat at the head of the table and turned to the rest of the group. “I am told Pulithēvan’s horde is amassed at our borders in the west.”

“Indeed, O Prince. In the past month alone, they have robbed eight of our caravans carrying taxes from the western districts. The loss of money, though sizeable, is only part of the problem. There have been some new developments in the night, we received message only this past hour—they have captured Kōmān Sīrālan’s son Nithilan and are holding him for ransom, in a remote hideout in the mountains.” said Nerivānan, the wizened Prime Minister. He was the oldest member of the council, having served the State since Kumudhan’s reign.

Aranvēndhan’s face visibly darkened. “Pulithēvan has gone too far this time. Sīrālan is a close ally. This vile deed must not go unpunished.”

“Prabhu, there is more—Kōmān Sīrālan attempted to retrieve his son, but he was wounded in the fray. His condition seems quite dire.”

“How did a common bandit manage that? Sīrālan is an excellent warrior, and has some fine soldiers.”

At that moment, the doors opened, and Emperor Kumudhan walked in. He was shorter than Aranvēndhan, but the resemblance was obvious. His thick wooden walking stick was purely ornamental, Kumudhan did not seem to need it as he strode to his seat at the table. The men all stood up, but Kumudhan waved them to sit down. “Continue, continue, do not mind this old man.” he smiled, and brushed his wispy white hair from his face.

“We were discussing Sīrālan, prabhu.”

“Ah, yes, I did hear.” Kumudhan turned to Nerivānan. “Send our physicians to Sīrālan. And some soldiers to escort him back to his fort.”

Nerivānan nodded. He gestured at a guard behind him, who bowed and sprinted out the doors.

Vagaimāran continued: “The attack on Sīrālan must have been an ambush. Mārthāndan’s visit has given us some unfortunate but valuable news—his horde is at least seven thousand strong.”

The Chancellor, Thiruvasagan let out a small gasp. “Seven thousand? How did Pulithēvan acquire so many men? Are we sure of the numbers?”

“Many of his men have little or no training. They are farmers and labourers from far-flung villages. It is likely Pulithēvan has only their swords, not their loyalty. This could be why he has now turned to looting tax caravans and demanding ransoms, to pay for these men.”

Aranvēndhan stood up, and spoke with controlled rage. “Pulithēvan must die. That vulture has pecked at our lands for far too long.” he paused, and took a moment to calm himself. “What do we know of his encampment?”

Vagaimāran, the General of the army stood up and pointed to a region west of Karkottai on the map laid out before them. “They have gathered at our borders in the forests along the Vellaru river. Chieftain Vēlan’s men say that his army consists mostly of foot soldiers and less than five hundred cavalry. But if he has amassed this large a group, he means to put them to use in some manner. It is best we retaliate at the earliest, and take him by surprise.”

“Indeed.” Mārthāndan agreed. “I already have our ūsippadai preparing as we speak. I shall take eight platoons upstream of their camp, and attack them from the west tonight. We need to drive them out into the open for our army to be effective against them. As they flee past this open expanse, Vagaimāran would lie in wait and attack them from the east. To the south, the mighty Vellaru will hinder their escape. We shall be able to capture them with ease.”

“You can cross the river at Easwarankoil, Māra.” Kumudhan said to the General. “I know the country there. The waters are fairly shallow near the temple ruins.”

“Of course, prabhu. I shall keep that in mind.”

“What of my role in this endeavour?” Aranvēndhan asked, staring at the map before him.

“My dear friend, this is but a small skirmish against untrained bandits, not hardened soldiers. We will handle this ourselves, kumārā.” said Mārthāndan.

“I agree with Senāpathi Mārthāndan.” Thiruvāsagan said, standing up. “This bandit Pulithēvan is no warrior, prabhu. He is unworthy of your attention. Why use a tiger to capture a rat?”

Aranvēndhan remained silent for a while. “Very well.” he stood up, and the Council all rose with him. “Begin preparations at once.”

“And I shall begin preparations for a feast upon Mārthāndan and Māran’s victorious return!” Kumudhan patted his stomach. The Council laughed heartily.

Father and son left the hall, and Mārthāndan turned to the rest of the table. “I shall depart with my corps at dusk and make for the hills upstream of Pulithēvan’s hideout. It shall be a swift ride in the night. I shall let loose the ūsippadai on them just before dawn, and drive them from the cover of the forest and onto the floodplains of Vellaru to the east. This is where Vagaimāran will lie in wait, and meet them in open battle. Pulithēvan’s men are not experienced soldiers—they will be no match for our warriors. Six battalions should be sufficient to rout these scum. It is flat country there, and Māran can crush them with ease.”

“Verily.” Vagaimāran struck the table. “I can make for the Solaipuram fort and begin preparations there. It is close to Pulithēvan’s camp, and is well-stocked.” Mārthāndan turned to the rest of the Council. They were all nodding slowly in agreement.

“Indeed.” Mārthāndan replied. “We can leave together under the cover of the night. I make for the hills, and you can take the north-western road to Solaipuram. Let us proceed, Māra.”

Minister Nerivānan also expressed his consent, and the Council disbanded to carry out the preparations. Ripunjaya followed Mārthāndan as they walked back to the barracks. Mārthāndan was quiet, lost in thought, and kept nodding to himself absently. As they neared the tents, Mārthāndan stopped. He turned back, smiling. “Come, Ripunjaya, I have something for you,” said Mārthāndan, and lead the way to his tent. He walked to a large chest in the corner, opened it and took out a sheathed sword. “Here, son. This is for you.”

Ripunjaya, pleasantly surprised, took the sword. The sheath was of dark hide, and inscribed with intricate patterns. He grasped the handle, and pulled the sword out slowly. The blade was curved slightly, its edge keen and polished. He noticed a small inscription near the grip on the blade. Looking closely, he realised it was his own name, written in the local script. He smiled and touched Mārthāndan’s feet. “A great honour, prabhu,” Ripunjaya said, bowing.

“A small token for saving my head.” Mārthāndan patted Ripunjaya on his shoulder. “Come, we have a lot of things to prepare. It will be a busy day.”

Outside, the entire kadagam was abuzz with activity. The soldiers were provisioning for their expedition, preparing their weapons and stocking up on rations. They walked to the back of the barracks, where the Mārthāndan’s corps had assembled.

The ūsippadai—the ‘needle corps’—were an elite regiment, trained in the art of gudayuddham, or covert warfare. Their talents did not lie in the open battlefield like the rest of the army—theirs was in the shadows, in the darkened halls and in the silence of the night. They were skilled assassins, feared by all and seen by few. The agents, called a kolaipadhagan, operated with a ruthlessness and efficiency that often belied belief. Their chief was Mārthāndan, who had personally trained many of the men in the regiment, and all were fiercely loyal to him. Mārthāndan explained the strategy to the captains, and they listened in rapt silence. With a quick sharp bow, they left to prepare their respective platoons.

“What now?” asked Ripunjaya.

“A nap,” replied Mārthāndan with a smirk. “A good meal and sound sleep are the first necessities before a battle.”

Read next—

Chapter 12 — To the forest

Year 63, Kaliyuga Present day The day rolled on, and the men slowly but steadily made ready. Towards dusk, the moon rose in the sky, shedding a dim light across the land. The bell in the barracks rang once, its report loud and clear. Mārthandan and Ripunjaya made their way to the palace, where Vagaimāran stood with his battalion chiefs near the gates. The…